I grew up in a small beach town on the Australian coastline, the kind of place where my greatest concerns as a child were whether the wind would be offshore tomorrow and if my favourite wave would hold the incoming swell. My upbringing was not unlike most in the sense that I was raised with certain biasses about the world and the people around us. When you’re young, it can be helpful to group people and things into buckets so that you can start to form a foundational understanding of your surroundings—we see this same attitude in the NFT space, but we’ll get to that later.

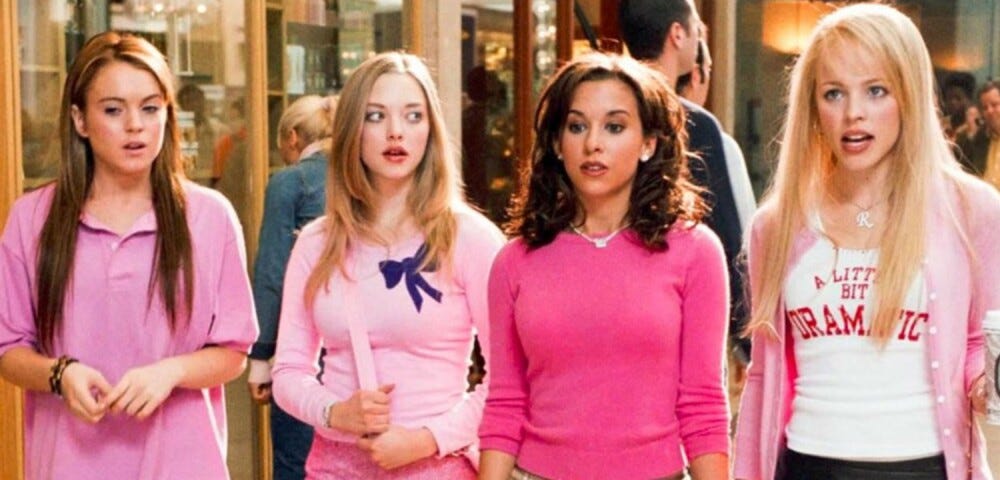

We tend to turn these into stereotypes that become quite sticky in our minds and can be hard to break as we age, even if they are no longer relevant. An example of this could be seen in my upbringing, where bodyboarders were always referred to as second-class citizens. We had many colourful terms for them, I’m sure many would be hard to understand from outside of the surfing community so if there’s a term you don’t understand in the following few paragraphs, you can presume it refers to bodyboarders.

In a house full of surfers, we always considered ourselves (and still do) as the top of the food-chain when it comes to buoyant ocean crafts that humans enjoy floating on. If there was a shark biscuit floating on our favourite break, we would comment among ourselves about the boring time they must be having just laying down on what could have been quite a fun wave. If we saw an esky lidder putting their fins on at the beach we’d be talking about how annoying it must be to have to walk out backwards so as to not trip over your own feet. And on smaller days where the waves didn’t have much power, we’d see a chin rider trying to paddle in and laugh to ourselves about them being better off on the beach than the ocean.

So I grew up to associate bodyboarding with not being an overly impressive endeavour, and in doing so created a stereotype that all bodyboarders are participating in the easier and more boring aquatic sport. This was all well and good as I continued to get better surfing most days of my life, until something happened when I was about 12 years old.

It was a seemingly normal day, the waves weren’t particularly great but they were good enough for dad and I to go out and justify an ice cream afterwards. In an absolute freak accident - that to this day I still wonder exactly how it occurred - I cut my foot open with the fin of my own board. It wasn’t a question of skill or an accident caused by another, just simple misfortune combined with the wind and my surfboard’s intent to come vertically down while my body rose to the surface, colliding the tip of my back fin to the top of my foot. Bleeding out on the beach in dad’s arms is something I don’t remember too clearly, but it was an interesting experience to go through. The injury was much worse than initially thought as I had severed the major artery in my foot, I won’t get too graphic here but it ended up with a 6 hour surgery and about 35 stitches if you include internal and external.

So there I was, a kid raised in and around surfing, now fearing the key pillar of my identity. My parents bought me a few boards over the years but I would always struggle to fall back in love with the sport and still carried an underlying fear for what could happen, the scar is still very present to this day and serves as a reminder. After the global financial crisis, we moved to a different suburb of the same town and I was sent to a new school. With all change comes new perspective, and my new school had a very different layout than the one I was at previously. In what was an absolute shock to my system, most of the cool kids were sponge riders! This didn’t really make any sense to me, after all I was raised to believe that bodyboarders did not command any semblance of respect.

I ended up making new friends, most of which were aquatic speed bumps (sorry, I know they’re getting harder but I’m still referring to bodyboarders). My best friend at the time was a kid called Adam, he lived nearby and one day I decided that it was time for me to get back out there and ‘surf’. My dad was a little concerned about the request to buy a boogie-board but he was absolutely thrilled to see me back out chasing waves with friends. Flippers in hand and some pathetic foam under my arm, I would go out every day with my friends and we would have a great time. I never really felt comfortable with a bodyboard and always felt somewhat anxious that ‘real’ surfers would look at me and think how I previously had, but it just felt right being back in the water. My love for the ocean quickly replaced the fear I had associated with it.

One day after a few months of bodyboarding, I decided that I was ready to get back on fibreglass and overcome the trauma that haunted me. I bought a surfboard and continued my routine with the same friends, going out every day after school regardless of conditions. Writing this now brings a massive smile to my face, as these days are very likely to be some of the best I will ever live; no dramas, no concerns, just great friends and shitty waves—all I had ever needed. Nowadays I look at bodyboarders in the ocean and I still very much hold the same biasses as I always did, but I know that there’s a large percentage of them that are great people, many are truly talented at what they do and some may even be going through a similar process that I once went through. The key lesson for me is that there are indeed bad bodyboarders, but that does not mean all bodyboarders are bad.

Human evolution primarily occurred in small groups of hunter-gatherers, the purpose being the mutual survival of both the individual members of the tribe and the tribe itself. We are hard-wired to seek out our own tribe, which in modern day terms are the people we feel share a common identity with us. This common identity can be people who live in similar areas, go to similar schools, work in similar careers or any number of other things ascribe value. In the physical world it can be quite easy to pick our tribes based on our interests, an obvious example of a modern day tribe can be seen in the passionate fans of a sports-team with one common interest.

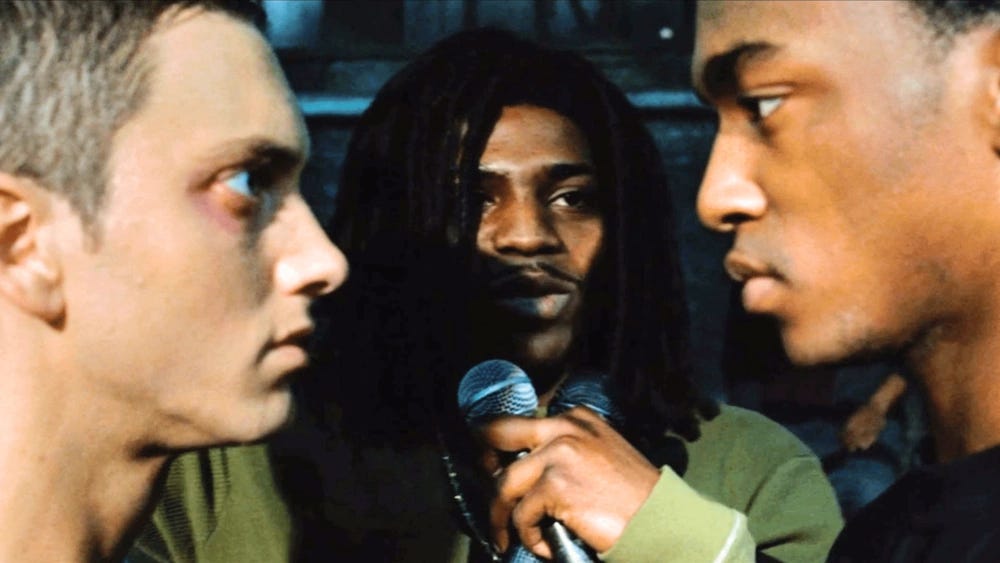

As the world around us progresses to be digital-first, so too do our identities. Many NFT projects are focused on having the best community available, resulting in the embodiment of modern-day tribalism. The recent NFT boom is heavily based on tribalism and the human desire to be a part of something bigger than themselves. One inevitable and unfortunate reality when developing communities of this size is that there’s bound to be bad actors. It is almost guaranteed that within any group of 10, 000 members that there will be some bad eggs, especially in an anonymous space. In some unfortunate cases, the actions of these few bad eggs can make the entire project smell rotten, even though they make up less than 1% of the participation.

Tribalism brings out the best and the worst parts of humanity. It can allow groups of people to combine and collectively produce something great or something terrible. It can be incredible to watch passionate communities being created seemingly overnight, connected through mutual speculation and a similar aesthetic (digital) identity. Unfortunately, what tends to happen to a lot of these groups is that rather than being appreciated for the work the founders do and the great people who are a part of the project, they will instead be associated with a select few cult-like leaders. Whilst it is only normal for leaders to form within large groups, the fact that a singular bad actor can plague an entire community is a concern.

There are many examples of this, on the ETH side we saw recently the impact that ZAGABOND had on the Azuki project by revealing himself to have somewhat of a shady (and previously unknown) past. Another example comes from the Pudgy Penguins and their original founder ColeThereum, causing quite a headache to holders when trying to separate. On Solana we’ve faced the same problems, founders going astray or losing interest after the initial sell-out has been the cause of many projects slowly fading away, in spite of having a very strong community backing.

Founders of a project will always have a large impact, but what about those simply holding an NFT? I have personally been turned off by many projects doing good things for no other reason aside from negative interactions with community members of the collection—sometimes all it takes is one. It is easy to say that this is not an intelligent thing to do, but it is very much a normal response when dealing with in-groups and out-groups. This can occasionally be justified for select groups that are able to curate their membership and therefore have the opportunity to vet new members to ensure their values are aligned with the existing group.

The issue that NFT founders face is that there is no ‘choosing’ your community, you can do your best to market towards a certain demographic, place importance on values, but there will still be bad actors. The interesting part about this for me is that most of the bad actors that we see as part of a project’s culture are also complete nightmares for the founders. I recently connected with a founder and let them know that I never bought into their project due to an individual being incredibly rude to me on Twitter while sporting one of their NFTs as their profile picture. The founder went on to tell me just how frustrating it was on their end having to deal with this individual, the contagion they created and the amount of time they had to allocate in an effort to deal with them.

It really opened my eyes into just how stupid I was to judge an entire collection by the actions of just one anonymous person on social media. It is akin to a seeing the heaven’s gate followers wearing Nike’s and deciding that Nike is a brand for cults. Collection founders fight these battles almost every day, and we as an ecosystem must realise that the minority are generally louder than the majority. Negativity bias is a cognitive bias that explains why negative events or feelings typically have a more significant impact on our psychological state than positive events or feelings, even when they are of equal proportion. We can use negativity bias to explain how this concept tends to occur, we place much more weight on the negative actions of the few than the positive actions of the many.

There are many such cases, and is why we regularly see people looking to call out the ‘BOOGLEs’, the ‘influencers’ or the ‘founders’ after hearing something from a third party about an individual that may fall into one of those categories. Tall Poppy Syndrome is all too common in any space where attention and engagement is the currency. The smaller the group, the easier the target. Some influencers (not all!) use this to growth hack their accounts, it is quite a simple formula to follow, and even easier if you are a Solana-native.

Step 1) Be a man of the people! Talk about how influencers are dumping on people, how all their problems are indeed caused by the rich and greedy with no exceptions.

Step 2) Take the most controversial opinion on any hot topic, Tweet in absolutes with confidence and sharp words. If it’s a real interesting one, why not take both sides of the argument? After all, the Twitter algorithm doesn’t care and most people who see your Tweet will only see the one that annoys them more.

Step 3) Bait any individual with a larger following than your own to interact or engage with your post, why not tag them aggressively?

Step 4) Monetise! You didn’t put in all that effort leeching to not secure the bag, did you? You now have a following that believes you are the good guy, which makes them the perfect people to dump on. Get that advisor cap on and lock in your 1000 whitelist spots king, your time is now.

There are many following the steps above who add fuel to the fire when it comes to narrative building in exchange for engagement. They play a very similar role to the traditional media when it comes to baiting clicks. I often think back to this line from Bombshell referring to how Fox News goes about finding a story.

“Ask yourself, 'what would scare my grandmother or piss off my grandfather?'”

We can rephrase this to a web3 context: “Ask yourself, ‘what would scare a retail market participant or piss off an influencer?” Combine this with ‘eat the rich’ and you have yourself a great Tweet.

In politics it can be abundantly clear that people choose their opinion based on allegiance to the group they consider themselves apart of, rather than making their own informed decision. People often select who will be their president based on who they like better as opposed to picking the overall party that is most aligned with their beliefs. We class people as ‘Republicans' and ‘Democrats’ as if the party is the sole reason they made their decisions. The US political system takes this to some of the more extreme ends, where we even saw a political identity being formed around whether an individual was to wear a mask or not.

What we need to be doing is judging the party leaders, and those who directly contribute—not those who follow the party. A fun recent example of how silly this is comes from the OFAC’s decision to sanction Tornado Cash. This means that any address or person that had used the service within the United States, or abroad if they are a citizen, had committed a crime. One Twitter user decided that it would be funny to send ETH that had gone through the service to celebrities and doxxed Twitter accounts—you can read about it here. This really highlights the absurdity that is judging things based on uncontrollable people or events. Categorising an entire NFT collection based on the uncontrollable actions of one individual would be as ridiculous as the OFAC convicting Jimmy Fallon for receiving ETH that he had no way of stopping.

The opposite can of course also be true where the majority of holders may be people that you do not want to connect with, but you should never completely write off all holders of the same NFT. We should always be trying to see the good in people while holding individuals accountable for their actions, irregardless of what JPEG they are represented by online.

As an ecosystem we need to move away from lazy stereotypes and move towards appreciating the individuals and project leaders that push the space forward. If you persist in judging the views of the few as the thoughts of the many you will lose opportunities for financial gain, new discovery and the very healthy exercise that is questioning your own biasses. Next time you see an ignorant post by someone with XYZ profile picture, I would encourage you to simply mute that individual and move on with your day. Remember that whenever you see a troublesome person online that frustrates you, know that the founder of the project they represent has likely lost sleep over them and there is simply no easy fix. The only way forward is to hold individuals accountable for their actions, not the brands they wear.

didn't read lol